|

Dudjom Rinpoche

Video Media Print Media Dalai Lama Penor Rinpoche Video Media Gyatrul Rinpoche Video Media Print Media Yangthang Rinpoche Video Media Print Media Khenpo Jigphun Video Media Getse Rinpoche Tulku Sang Ngag Video Media Khenchen Namdröl Video Media Penam Rinpoche Lobpön Nikula Kusum Lingpa Chagdud Rinpoche Drugchen Rinpoche B. Alan Wallace |

Thubten Trinle Palzang, the fourth Dodrubchen Rinpoche, was born in 1927 in the Golok province of Dokham in Eastern Tibet, and was recognized by the Fifth Dzogchen Rinpoche, Thubten Chökyi Dorje, who had prophesied his birth. At the age of four, he was enthroned at the Dodrupchen monastery.

Dodrubchen Rinpoche reportedly had visions of the Buddha as a young child shortly after being enthroned. This was seen as an example of his attainment. In addition to studying at the Dodrupchen monastery, he also studied at the Dzogchen monastery. Among the many great masters from whom he received teachings were Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, the Sixth Dzogchen Rinpoche, Shechen Kongtrul, Dzogchen Khenpo Gönpo, and Gyalrong Namtrul Rinpoche. From Yukhok Chatralwa, who was a manifestation of Vimalamitra, and from Apang Tertön, he received the final teachings on the meaning of Dzogpachenpo, which he practiced under their guidance. At the age of nineteen he made a pilgrimage to Central Tibet and completed a retreat at Tsering Jong. He then built a Scriptural College at the Dodrupchen monastery. He also provided the woodblocks for the printing of the Seven Treasures of Longchenpa. Concerned about the political unrest that preceded the Communist Chinese occupation of his homeland, he left Tibet in 1957, and sought refuge in Sikkim, India.

|

|

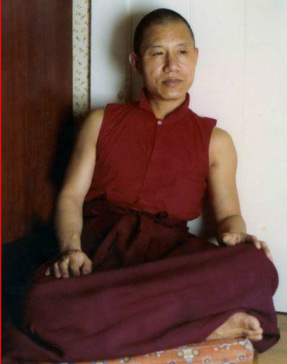

Zenkar Tulku, Dodrubchen Rinpoche, and Yangthang Rinpoche

|

|

Dodrubchen Monastery

|

|

The following is an excerpt of a teaching based on a text by Jigmed Tenpe Nyima, the Third Dodrubchen Rinpoche on the merits of cleaning a temple:

... The whole spiritual purpose of cleaning (the temple) is to realize all the stages of spiritual insight and ultimately attain buddhahood. Such realizations can only come about if our mental, emotional, and karmic obscurations are purified. That is why purifying the mind is just as important as the realizations themselves, for without that purification, spiritual insight will be impossible. Chudapathaka was one of the Sixteen Arhats, from Buddha Shakyamuni's time. He was ordained into the Sangha, but was very stupid before he became an arhat, so stupid that he could not learn or memorize even one word of the Dharma. Eventually the Sangha decided that they could no longer have him as a member. This was an ethical decision rather than a reflection of their lack of compassion or unwillingness to help him. The Sangha lived on the offerings of devotees, offerings that consisted mainly of food because the monks and nuns of those times did not own anything except their robes and a begging bowl. The lay people made offerings out of devotion, faith, and trust in the learning, purity, and accomplishments of the Sangha. If any member was not qualified, accepting such offerings would be a deception and a source of bad karma for both that person and the Sangha as a whole. When Chudapanthaka was asked to leave the Sangha, he was saddened and depressed, and began to cry. The Buddha walked past, saw him crying, and asked his followers what had happened. When the Buddha was told of Chudapanthaka's predicament, he took pity on him and asked him to remain in the Sangha and perform the role of cleaning the monks sandals. Chudapanthaka cleaned their sandals for many years with a focused mind. He was happy because he was still able to live as a Sangha member. After many years of cleaning with one-focus, one-concentration, and one-dedication, a thought suddenly came into Chudapanthaka's mind: "Is this dust the dust of earth or the dust of desire?" Then he immediately had this realization: This is the dust of desire, and any learned one who fully abandons that dust is truly heedful of the Tathagata's teaching. This is the dust of anger, and any learned one who full abandons that dust is truly heedful of the Tathagata's teaching This is the dust of ignorance, and any learned one who fully abandons that dust is truly heedful of the Tathagata's teaching. When those lines came into his mind, he instantly became an arhat. He did nothing but clean the sandals of the monks and nuns with one-pointed mind, repeating the phrase, "I'm cleaning the dust, I'm cleaning the dust." This was enough for him to attain liberation, when he saw through his actions to the true nature of existence. The purpose of cleaning a temple is to clean the mind. If we can purify our mind, the whole universe will become pure, because whatever negative emotions, attitudes, objects, enemies, or dirt there is outside ourselves will be transformed when our minds become pure. Our mind will become pure when we realize the true nature of the mind. That will happen only by working hard on external situations, such as cleaning a temple. We can realize this pure mind through cleaning meditation by depending upon three factors. The first factor is the field, which refers to material objects, such as statues, images of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, or the temple itself. The second factor is our mental attitude or intention, and the third is the actual application of the cleaning... See the complete teaching on the Merits of Cleaning a Temple |

Advice for a Dying Practitioner

By Dodrubchen Jikmé Tenpé Nyima

You will need to make preparations before the time comes to pass away. There are many aspects to this, but I will not go into too much detail here. Briefly then, this is what you should do as you approach the time of death.

Think to yourself again and again: “Whether death comes sooner or later, ultimately there is no alternative but to give up this body and all my possessions. This is just how it is for the world as a whole.” Thinking along these lines, sever completely the bonds of desire and attachment. Confess all the harmful actions you have committed in this and all your other lives, as well as any downfalls or breakages of vows you may have incurred, wittingly or unwittingly, and make repeated pledges never to act in such a way in the future.

Do not feel nervous or apprehensive about death. Try instead to raise your spirits and cultivate a clear sense of joy, bringing to mind all the positive, virtuous things you have done in the past. Without feeling any trace of pride or arrogance, celebrate your achievements over and over again. Dedicate all your merits and make repeated prayers of aspiration, so that in all your future lives you may be able to take to heart the complete path of the supreme vehicle, with the guidance of a virtuous spiritual friend, and with qualities such as faith, diligence, wisdom, and conscientiousness—in other words, all the most perfect circumstances, both outer and inner. Pray too that you never fall under the influence of evil companions or destructive emotions.

The texts of the Vinaya explain that one of the principal causes for taking a supreme form of rebirth, as one who leads a disciplined life in the presence of the Buddha for example, is to make prayers and aspirations at the moment of death. This is why it is said that “whatever is the closest and whatever is the most familiar” will have tremendous power. ...

... At the actual moment of death it will be difficult to gather sufficient strength of mind to meditate on something new or unfamiliar, which is why you must choose an appropriate meditation beforehand and train until you are familiar with it. Then, as you pass away you should devote your thoughts to the meditation as much as you possibly can, whether it is remembering the Buddha, focusing on the feeling of compassion, cultivating the view of shunyata, or remembering the Dharma or the Sangha. In order for this to happen successfully, it is also important that you train yourself beforehand to think, “From now on, as I pass through this critical juncture of the time of death, I will not allow any negative thoughts to enter my mind.” ...

See the complete text of Advice for a Dying Practitioner

By Dodrubchen Jikmé Tenpé Nyima

You will need to make preparations before the time comes to pass away. There are many aspects to this, but I will not go into too much detail here. Briefly then, this is what you should do as you approach the time of death.

Think to yourself again and again: “Whether death comes sooner or later, ultimately there is no alternative but to give up this body and all my possessions. This is just how it is for the world as a whole.” Thinking along these lines, sever completely the bonds of desire and attachment. Confess all the harmful actions you have committed in this and all your other lives, as well as any downfalls or breakages of vows you may have incurred, wittingly or unwittingly, and make repeated pledges never to act in such a way in the future.

Do not feel nervous or apprehensive about death. Try instead to raise your spirits and cultivate a clear sense of joy, bringing to mind all the positive, virtuous things you have done in the past. Without feeling any trace of pride or arrogance, celebrate your achievements over and over again. Dedicate all your merits and make repeated prayers of aspiration, so that in all your future lives you may be able to take to heart the complete path of the supreme vehicle, with the guidance of a virtuous spiritual friend, and with qualities such as faith, diligence, wisdom, and conscientiousness—in other words, all the most perfect circumstances, both outer and inner. Pray too that you never fall under the influence of evil companions or destructive emotions.

The texts of the Vinaya explain that one of the principal causes for taking a supreme form of rebirth, as one who leads a disciplined life in the presence of the Buddha for example, is to make prayers and aspirations at the moment of death. This is why it is said that “whatever is the closest and whatever is the most familiar” will have tremendous power. ...

... At the actual moment of death it will be difficult to gather sufficient strength of mind to meditate on something new or unfamiliar, which is why you must choose an appropriate meditation beforehand and train until you are familiar with it. Then, as you pass away you should devote your thoughts to the meditation as much as you possibly can, whether it is remembering the Buddha, focusing on the feeling of compassion, cultivating the view of shunyata, or remembering the Dharma or the Sangha. In order for this to happen successfully, it is also important that you train yourself beforehand to think, “From now on, as I pass through this critical juncture of the time of death, I will not allow any negative thoughts to enter my mind.” ...

See the complete text of Advice for a Dying Practitioner